Khan Schoolcraft, 33, moderates a Facebook group called “AI Boometrap,” which collects examples of the genre (the sarcastic name refers to demographics that seem to be tricked into thinking the images are real). gets eaten—though anyone can fall for it). Schoolcraft has seen it all. “Tiger Jesus rescuing his beautiful cabin crew from a ship that is slowly sinking into the mud,” he says, for example. “You'll see, like, a half-human, half-babe hybrid eaten alive by fire ants, and people are commenting, 'Oh so beautiful, I love it. Amen. God bless.'”

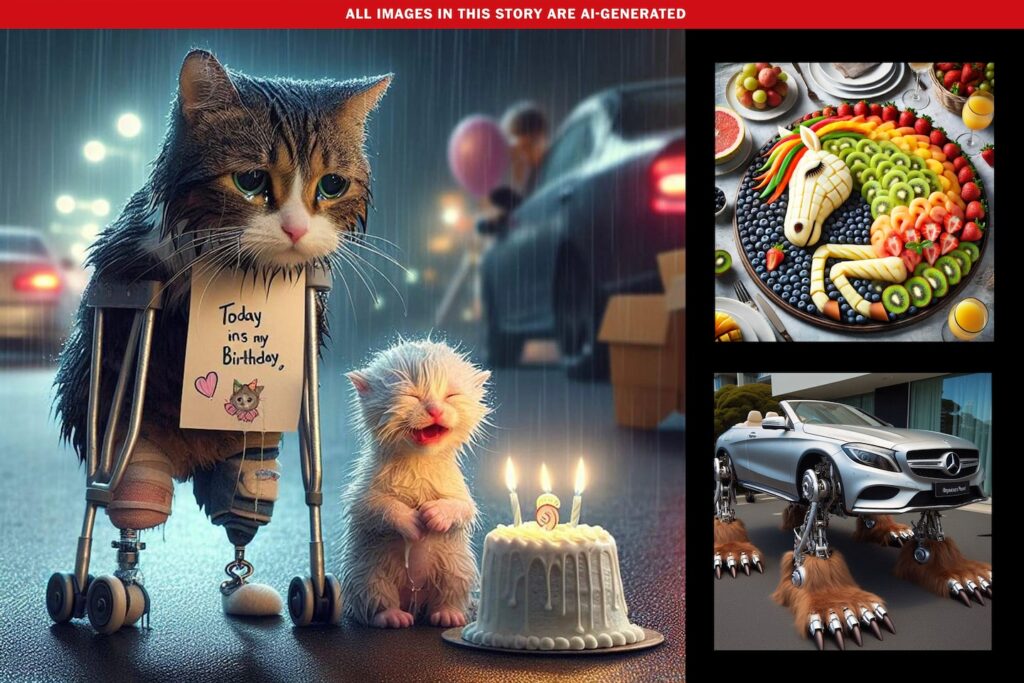

Even the more prosaic images have a certain aesthetic – Like The tendency of AI-generated human quadruplets or centenarians to ask for birthday wishes with their own hand-made cakes, the designs of which are at odds with the map of reality. People somehow don't see, or look past, the obvious signs of software-generated fake and real.

Balanced by the craziness of the content Jonathan Gilmore, professor of philosophy at the City University of New York and co-editor of the Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, says “this incredibly simple, realistic style” is very easy to follow.

These images are “slop,” the tech world's term for the image equivalent of spam. But they are also a new kind of realism. From a certain point of view – if your interpretation is broad enough – they can even be art. no good Art, by any definition, but they raise interesting philosophical questions about how we think about and categorize images produced by AI.

Maybe these images — designed to draw attention to scam pages or ad-laden clickbait sites — are a sign of this. The rise of a “zombie internet” populated by AI and bots. But that's not what we're going to talk about.

We're going to talk about why they look the way they do: flat, insidious, unremarkable. There's a good reason one of the AI image generation programs is named DALL-E (a fusion of Dali and the title character of the Pixar film “WALL-E”). Everything feels surreal these days. Can these unreal images lead us to an obvious truth?

TFrench writer André Breton wrote in his 1924 “Manifesto of Surrealism” that the genre exalts the “higher reality” of the unconscious mind—that dreams and reality can merge to create one. The fact is that one way or another More real But what happens when the entity creating the actual image is not human? What if the creator himself is real?

“These are serious questions in the philosophy of art right now,” Gilmour says. “The questions cut to the core of what we think about art, and what we mean by art, and what we think art can do for us. Should.”

Art should make us feel something. On this metric, Facebook Slope actually succeeds, but in the most obvious, understated way. Because these images are designed to get people to interact with specific Facebook pages, they tend to tug at the heartstrings with the theme of empathy or titillation: puppies, babies, patriotism, religion, seniors, Attractive people. It's a well-trodden area of cringe and kitsch.

“Because it's so crass, it's fundamentally conservative, which might seem counterintuitive because it's so weird and unusual,” says Gilmore. Each picture is its own melodrama, which engages the emotions of the viewer.

That stands for conservative with a lowercase “c,” though AI slop is usually politically conservative as well: Schoolcraft's Facebook group is full of examples of trope-slating, anti-LGBTQ+, pro-Trump schlock. Is. A recent example: an old man in an American flag shirt and MAGA-esque red hat, reading the Bible to a dozen attentive drag queens. At a glance, the image may look like a graphic illustration. But the letters on his hat are smudged, and he has only three fingers on each hand.

Robert Hopkins, a professor of philosophy at New York University who studies aesthetics, offers some more questions to examine whether AI-generated works Art with a capital A.

“Does it have the power of real expression?” Asks Hopkins, “Does it express feelings and moods and ideas, and make them clear to you in a way that is distinctly artistic? … Is it having an interesting conversation with previous art?”

Humans what Create AI art, in a sense: they must piece together a description, or prompt, to tell the AI what to do. In this sense, AI is a tool, A kind of magic, like an automated paintbrush.

Art history is full of skeptical responses to new technology. “The machines have come, art has fled,” said photographic artist Paul Gauguin. In his early days, critics believed that artists “could never create great art from photography, because all the photographer had to do was set up the camera and … hit the shutter,” says Gilmore. . “It was clearly wrong.”

Using any artistic tool requires skill. What separates “real” AI art and social media slop is refinery and context.

Polina Kostanda, a 45-year-old Ukraine-based AI artist who posts her work as Polly in Wonderland, also creates surreal, surreal and dreamlike images: grandmas with mermaid tails, frogs smoking cigarettes, pepperoni. Pizzas are growing like wild flowers. These descriptions might fit the weird crap reposted on “AI Boometrap”, except that Costanda sells prints and NFTs of his work, and is represented by a photo agency in Milan. She says via email that she aims for viewers of her work to confront the limits of reality and “encourage them to go beyond their usual perceptions.”

Costanda's work—for which she uses AI image-processing software called Midjourney—is free of the flat effect that plagues the social media art you see on Facebook, because she knows what to do. How to create a skillful prompt that evokes true photographic quality. Besides that While determining the subject, she will also mention a film and camera as part of the prompt. “For example, Kodak Portra 800,” says Costanda. “And the camera this photo was taken with, for example: Hasselblad 503CW.”

What pushes an AI-generated image into the realm of art, she says, is whether it conveys a message, and whether it “captures the soul.”

“There are a lot of 'dead' physical paintings and images, with no idea or message,” says Costanda. “And there are 'live' AI images”—images full of depth and meaning— “What can be confidently called art.”

IIf some images are alive, and some are dead, here's AI's Schrödinger's Cat: This Month Photographer Miles Austry won — and then got disqualified from — an AI photography contest. He submitted. A surreal image of a flamingo with its head tucked into its arm to the point where it appears to be just a ball of feathers with legs – as in a hilarious AI misinterpretation of what the bird is. On his website, Astray said he posted his photo “to prove that man-made material is not losing its relevance, that Mother Nature and her human interpreters can still beat the machine.” And that creativity and emotion are more than just a string of numbers.”

The flip side can be true, too: these bland, cute Facebook photos can, in the right context, become real art. Think of them as the digital equivalent of ready-mades, for artist Marcel Duchamp's work with commercially produced objects like bicycle wheels or urinals. A clever artist can imitate or exploit the style of these images to comment on social media, consumerism, patriotism or religion. (Or — like the members of AI Boometrap — for memes.)

Could AI be a Facebook Slope? Beautiful? Vadim Meyl thinks so. Mel, a researcher with Central European University, published a paper in February saying “artificial intelligence stands as a defining beauty of our time.” The beauty of the system itself – not just its outputs, but also its code and its algorithms that enable machine learning. “is of a new kind,” writes Maile in his treatise, “which may be fully understood in future centuries.”

The Facebook slope, Mail wrote in an email, is more a matter of intent than aesthetics.

The dreamy, whimsical, thought-provoking realism “that once seemed reserved for intelligent people of their generation is now accessible through AI,” he says. But if these qualities become more associated with anonymous scammers on phishing pages than with artistic genius in galleries, it can give us realism fatigue. Mail writes: “We would expect. [the] 'Unexpected' and lose. [the] The Wow Effect of AI Art.”

OhAs an artistic tool, AI is still in its infancy. We're still not sure how to define it, says Hopkins. Will it be judged alongside the various forms of handmade art that it imitates, or will it be in a category of its own?

An argument for the latter is that we judge works of art not only by how we experience them, but also by Our understanding of how they are made.

“We sometimes value works of art when they are the result of great struggle, or talent,” Gilmour says. The concept of AI art is that it is “undermined by the fact that it was so easy to create.”

Mel believes that art created by human-made algorithms should not be treated differently from art created by human hands. He sees AI as a tool like a potter's wheel. “It works within the parameters set by the human creator,” he says.

So in Mel's eyes AI is slope art. This is really amateurish, really fascinating, really bad art – the most amateurish art of its kind that humans have created on media in all of history.

Put aside the AI generator's tendency to add or subtract fingers and its ability to cheat. The question, then, is: Why are there so many? AI creators – from scammers to professional artists – stuck on this flat, cheesy, sometimes hackneyed form of realism?

“With this absolutely vast, seemingly limitless ability to create a visual image, the work looks very traditional,” Gilmour says. Disturbing and unusual, yes, but somehow “so boring, so familiar.”

For example: Several recent posts from a Facebook page simply called “Fascination,” apparently run from Armenia. The posts depict the same subject — a little boy who, with skills beyond his years, has allegedly painted a coastal landscape — with the same caption: “My new artwork, brah Please appreciate it.” The babies look real enough, but the details of the photos are a giveaway. One of the lighthouses sticks out from the canvas. The ground shown below Chitral is also rendered in brush strokes.

The picture is not real. The boy is not real. The fake boy painting is not real. The posts are modern renditions of the famous Rene Magritte work “La Condition Humaine,” a painting within a painting that blends so seamlessly into its background that you can't tell which part of the scene is which. is real

“You're so talented,” said one commenter named Daphne They Real?) replied to a post. “That's what I call a work of art.”