This article was originally published on Common Edge.

The rise of generative AI has given every design educator ample reason to rethink what to teach and how to teach it. Training an architect is a long process, and mapping it to an uncertain future is a daunting task. Researchers at OpenAI, DeepMind, Meta, and similar companies are constantly surprised by the rapid growth and sometimes unexpected capabilities of their AI creations. If even the creators don’t know how fast the future will come, it would be fun for any of us to claim it. AI will do X. or AI will not be able to do Y. Over the next decade, which is how long it takes to actually train an architect.

The conversation about what and how to teach is already contentious, and must evolve with technology. Parts of this will remain unresolved until the implications of these new technologies are more clearly understood. However, there is another, simpler conversation: what? no to teach.

Related Articles

Can artificial intelligence systems like DALL-E or Midjourney perform creative tasks?

This discourse has also been contested historically and is inseparable from the debate about what to teach. But in my own teaching and conversations with colleagues, there seems to be a consensus among design faculty that some things should no longer be taught in architecture school. These anachronisms persist in most schools because of institutional and cultural inertia, and perhaps because schools are able to produce great architects despite them.

However, AI will change this calculation. It gives us new arguments to purge some of the more ossified practices of design culture. What was a frustrating anachronism yesterday can become a liability tomorrow, compromising our ability to train young architects and their ability to continue in the profession. With AI, we finally have the means and purpose to get rid of the three things that are traditionally endemic to the educational process.

Maswakism

If creative AI speeds up the process of visualizing and producing designs by a factor of 10, it would be a great tragedy to allow students to use all of that increased productivity to use their instincts. Overnight and ignore yourself. Despite the efforts of many design educators to curb these instincts, the culture of self-neglect and burnout in design school has proven to be a persistent and intractable problem.

Part of the problem is certainly that there are still valuable lessons to be learned in the more masochistic parts of studio culture. Architecture school taught me to keep iterating, taught me to “kill my darlings,” taught me that there is always a better solution to any problem, if I can be open to it. Once you make that intense commitment to improving your work, staying overnight seems like the logical expression of that commitment. It was justified, but it wasn’t Reason This was because it takes much longer to test, prove and demonstrate an idea than it does to have the idea in the first place. The human brain can receive inspiration in less than a second. But to test, prove and demonstrate this idea requires action in the form of drawings and models.Very of them. So if you care about your thoughts, you’ll start a pot of coffee.

This may seem reasonable—at least to anyone who has been to architecture school—as long as you ignore the downstream effects. When you stay up many nights in a row trying to test and prove a brilliant idea, your creativity is constantly eroded, compromising what that second or third brilliant idea might be.

The importance of sleep to creativity cannot be overstated. Research consistently shows that a relaxed mind is better able to generate new ideas, solve complex problems, and think critically. Compared to machines, lack of sleep would be a strategic disadvantage. If “creativity” is to become an interior part of the citadel of architecture, we must defend it at all costs by defending sleep and retiring overnight.

But how do we work?! Every architecture student everywhere screams. In the AI future, an architecture student’s day looks like a contemporary writer’s day. For a creative writer, inspiration and production often flow as one process. Think, type, repeat. Revise later. Most writers stick to a disciplined schedule designed to maximize creativity, recognizing that the human brain can only be creative for so long and needs things like sleep, exercise, and food. Is. Haruki Murakami wakes up at 4:00 a.m. and works only five or six hours a day. In the afternoon he runs, or writes, or listens to music. Maya Angelou had a similar practice, writing only from 7:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m., and was so committed to her focus that she would find a hotel and “a room with only one bed.” Small, modest room, and sometimes, rented. A facial basin if I could find it. Once she left her desk at 2:00 each day, she lived a normal life. She ate dinner with her husband and slept well at night. No one could argue that Murakami and Angelo were uncreative or unsuccessful. And the structure of a great novel is no less complex than a great building. would have

Imagine if an architecture student only worked six hours a day, but the entire period was devoted to pure creation, while machines took over production?

As AI increasingly takes over the mechanical aspects of design, humans must focus their efforts only on things that humans can do. If you believe that creativity is one of those sacred cows, let’s break this ugly tradition and make it better for it.

So ask your students to leave the studio at a reasonable time and go home. Insist on it. Insist that they make their design, do their best, and then go home, or go out. Advise them to meet other people their age, preferably in fields other than architecture. Ask them to take up a hobby, or join a club or sports team. (Even one A cappella group, if they absolutely must.)

Tell them what you know: Life is what architecture is made of. Love, loss, danger, failure—these are the engines that power any true creativity. And sleep is the motor oil that keeps them working. So get some sleep, and let the machines work through the night.

Image fetishization

For most of prehistory, architecture was primarily a local experience, appreciated through the settlement of its sites. However, with the advent of mass media, architecture began to move toward an image-based culture, more than almost any other professional discipline. This change is attributed to the way the mass media divide different types of professional success: commercial success (making money), professional success (being respected by one’s peers), and cultural success ( valued by the wider culture).

In most professional disciplines, these three types of success typically follow a sequential path. However, there is an alternative path to architecture, which I will call Path B. This passage breaks the traditional order and, as far as I can tell, is unique to the architecture. Through Path B, an architect can achieve cultural success by earning the respect of his peers, even if he has limited commercial success or architectural projects.

With enough professional and cultural success, one can. Then Achieve commercial success, as clients will line up to hire the famous architect whom all other architects admire. (It’s always interesting that some architect can win the Pritzker Prize—a prize that apparently “Architects whose architectural work demonstrates a combination of these qualities of talent, vision and commitment have made lasting and significant contributions to humanity and the built environment.With a very limited portfolio of works built mainly on the strength of his publications and theoretical works. Equally interesting is how the same architect Then develop an extensive practice with large and expensive built projects).

Sure, architects can, and often do, go the traditional route. But architects also have a path B that is hard to imagine in any other professional discipline. We wouldn’t know who Warren Buffett was if his early forays into investing had lost all his early clients money, and we wouldn’t know who Johnnie Cochran was if all his early clients had gone to jail. were

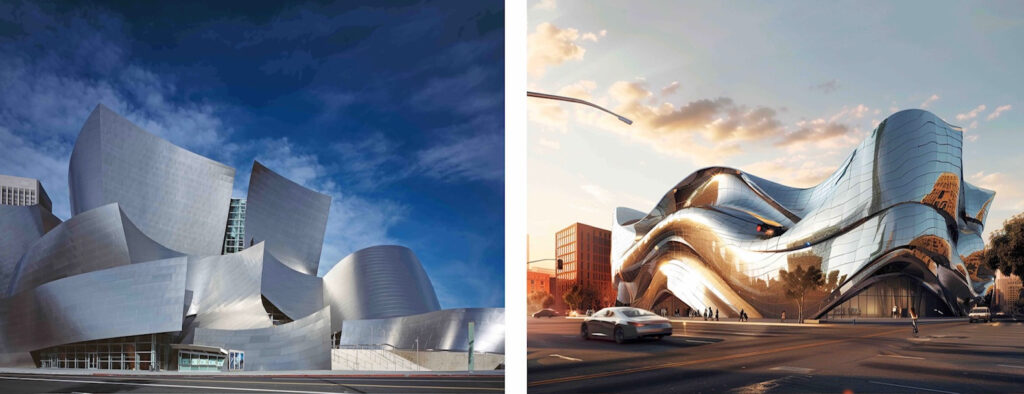

Path B’s existence in architecture enables and encourages the fetishization of imagery. If your goal is commercial success. first, You’ll focus on the things the client cares about, like meeting budgets, and building buildings. If your goal is professional success first, you’ll focus on things that other architects care about, such as new ideas, forms, materials, and other types of experimentation. Any novel is much more easily constructed and conveyed through images than through wood, brick, concrete, metal and glass. So architects have come to accept the image of one. thing as sufficient proof of the concept of the thing itself. One can gain notoriety by producing and disseminating photographs of all the new buildings one could never have imagined without bearing the burden of their completion. Then, when one becomes famous and in demand, one can take on the task of realizing these ideas in a constructed form.

The rise of AI in architecture fundamentally challenges the viability of pursuing Path B. With AI-powered tools capable of creating stunning, novel renderings based on text prompts, producing impressive architectural images alone no longer indicates this level of creativity and innovation. He did it once. As a result, it will become increasingly difficult to obtain an initial definition primarily through imaging. How could it not be? We won’t give our collective praise to the architects who create work that a teenager with a ChatGPT subscription can easily do.