“Oh, stop it—you're embarrassing me,” said a throaty voice appreciatively. Barrett Zoff, who had praised, looked pleased. As it should — Zof represents OpenAI, the company behind voice.

ChatGPT-4o, OpenAI's latest chatbot iteration, isn't an improvement on appearing intelligent—it's an improvement on appearing emotional. “We're looking at the future of interaction between us and machines,” promises Meera Murthy, OpenAI's chief technology officer.

ChatGPT-4o is one of a wave of new conversational AI, including the rollout of Meta AI last month. Mark Zuckerberg predicted upon its release that “by the end of the decade, I think a lot of people will be talking to AIs most of the day.” Zuckerberg's claim (self-aggrandizing though it may be) echoes much of the research on chatbots. A 2022 study published in Computers in Human Behavior claims that these conversational AI technologies “could meet the same needs as human acquaintances” and “soon provide personalized social support to multiple users. “

As larger language models improve, Zuckerberg and others suggest, humans will increasingly enjoy interacting with them — a shift perhaps identified by US Surgeon General Vivek H. Murthy. It will also reduce the “epidemic of loneliness”. According to this line of thinking, technological innovation is the only thing standing in the way of sustainable, fulfilling human-AI interaction.

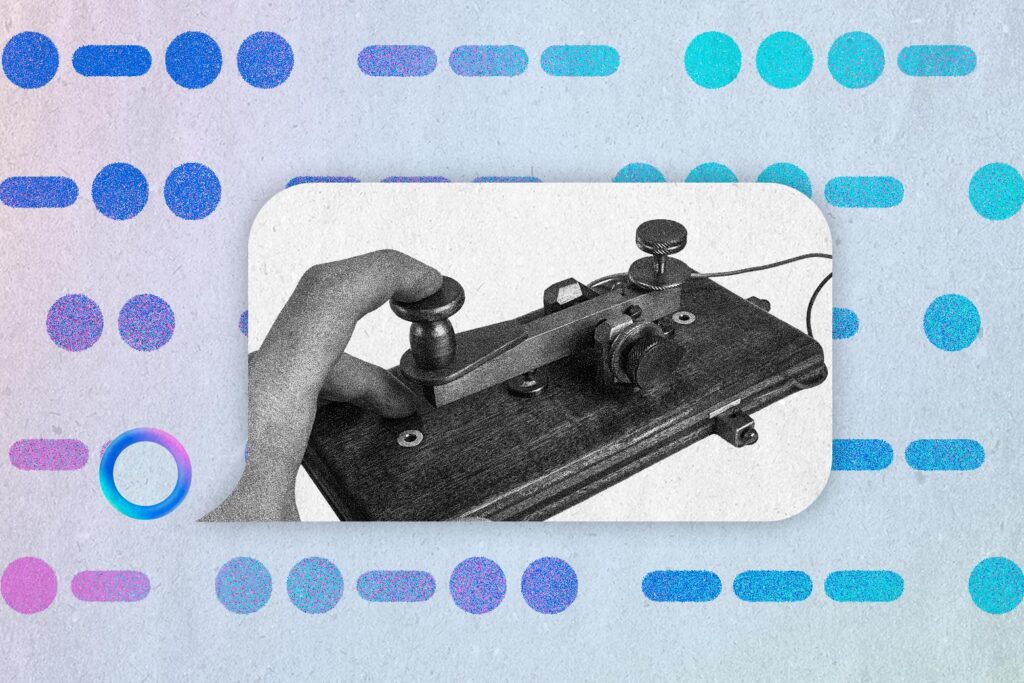

However, the long history of human communication suggests another factor: Expectations We bring these interactions to the fore through more than 100 years of interaction with and through machines. Ever since the Victorian telegraph created real-time communication over a distance, humans have been trying to imagine the person who created the words they are reading. These imaginations have created the standards for authenticity that we bring to our interactions with chatbots today—and it goes beyond LLM authenticity. I don't know that chatbot conversations will ever replace human isolation, but understanding their potential requires looking at how this historical context has shaped our human interpretations of technology.

The spread of telegraph lines during the mid-19Th The century presented a new possibility: two people could have a synchronous conversation hundreds or even thousands of miles apart. They may already know each other and enjoy this quick form of communication, or they may be complete strangers. It was the latter possibility that captured the public imagination.

Telegraph operators were often women, and this new form of communication gave rise to what we now call catfishing: luring someone into a relationship by misrepresenting oneself. The Telegraph ushered in innovative opportunities for women's liberation and, with it, new metrics—and a new urgency—for separating the real from the fake.

For example, a headline in the February 13, 1886 issue of the trade journal The Electrical World warned of the “Dangers of Wired Love.” The article states that Maggie McCutcheon, a young Brooklyn telegrapher, was “flirting” with Frank Frisby. But McCutcheon's father discovered that Frisbie had married into a family in Pennsylvania. The article details the father's efforts to keep McCutcheon away from the wires that allow him to communicate with the Frisbee, and McCutcheon's determination to find his way to the telegraph machine.

McCutcheon's father tries to control him by sending him to the Catskill Mountains. He fires her from her post at his telegraph office and drags her from a friend's house, threatening him with violence. There is little mention of Frisby other than his alleged family, who conveniently live far away. Like a conversational AI, he is random, haphazard, existing only in and through the telegraph machine.

The main points of this short story revolve around the popular myths of the time. Often called “techno-romance,” these stories and novels illustrate the possibilities offered by the apparatus: stripped of the trappings of beauty, status, and family, does the telegraph allow someone to truly know and be recognized in return? Makes it possible to go? Or does it introduce a new type of forgery, the ability to pretend to be someone, for whom there is no evidence?

Ella Cheever Thayer's 1879 hit novel Wired Love: A Romance in Dots and Dashes suggests that both may be true. Recounting the courtship of two young telegraph operators, Clem and Nathalie, it shows how a bond can be formed just by exchanging words. But that doesn't mean expectations just evaporate for the body at the other end. Midway through the novel, Clem shows up unannounced at Nathalie's office. Far from the handsome man he portrays, he walks around with “an air of cheap assurance” and flashes his trinkets, looking for cheap cologne, hair coated in bear grease. Natalie isn't just scared — she feels betrayed.

And it turns out she has been. The visit was merely a prank by another telegraph operator, who was eavesdropping on the communications. Eventually, the real claim emerges, and the couple's love survives the transition from broken strings to everyday life. The possibility of deception remains, but the novel ends by affirming the validity of technological romance: true connection transcends material boundaries and can only be exchanged for words, for sight.

Published 20 years later, Henry James' novel “In the Cage” offers a more cautionary tale. At its center, a young, unknown telegraph operator looks on as the beautiful, married Lady Braden, hoping that no one will heed the messages of the heroic Captain Everard. But the narrator—technologically astute and, by proxy, fancies himself a savvy reader of people—understands the secret love story.

Disconnected communication seems to win the day once again, but the story takes a turn. Lady Braden's husband dies, and she pressures Captain Everard to marry her, despite his declining interest and mounting debts. The telegraph operator is shocked by what is revealed about the grim realities of high society existence. No longer bits of information transmitted over wires, these lives become personal, and feel suffocated and lacking. The romance of the telegraph seduced both Lady Braden and the telegraph operator, but the temptation was fleeting and disappointing. The novel ends with the telegraph operator leaving behind his “dreams and delusions” and “returning to reality”.

Although the telegraph has long since been replaced, modern-day interactions with chatbots are similar to those early interactions between wires: they are also random communications that occur purely through language. As in 19Th century, when new technology is introduced, we have to reset our standards for trust. The more human-like a chatbot looks, the harder it can be to keep in mind that your conversation doesn't have feelings for you or anyone else.

As telegraph users discovered, with new possibilities for communication came new possibilities for misinformation, unhealthy dependence, even fraud. An authentic conversation with an AI—which has artificiality in its name—should look different than an authentic conversation with a person. Not just a skillful imitation, but an entirely unprecedented type of interaction.

Early research suggests that over-reliance on conversational AI for social fulfillment could lead to “de-skilling,” a loss of the ability to connect in person as chatbots take over to keep the conversation going. has been programmed. Creating chatbots in the image of human conversation can lead to a one-sided belief in the authenticity of the relationship — an unfamiliar form of fraud in which users only harm themselves.

The past informs the assumptions and expectations we bring to conversational AI, so with this knowledge, we can establish historically informed criteria for assessing the authenticity of virtual relationships. Unlike the telegraph, however, there is no longer a human on the other end of the line. We need to re-evaluate these mediated communications rather than turning to them as direct substitutes for human contact. The techno romance of our time is not with a stranger on the other end of the wire. Now the wire only goes to one server. Form