Terrible, soul-sucking ads are written, created, and rejected by the public all the time. This is a different one.

Apple's “Crush” commercial, which was unveiled last week and is no longer scheduled to air on TV in the U.S. because people really, madly, hate it, is a miss, or a flub. is something bigger than Contrary to Apple's vice president of marketing communications Tor Myhren's walkback last week — “We missed the mark with this video, and we're sorry” — the new iPad Pro commercial is very much about being scary and honest. Hit the mark harder. Apple's vision of the future.

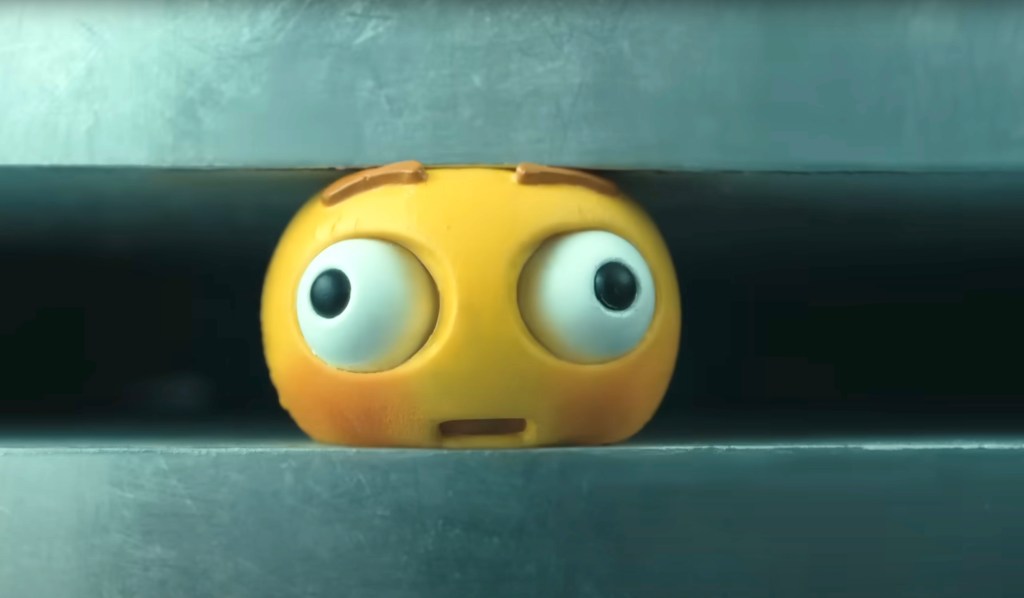

Take 60 seconds to watch it (it's all over the place, including YouTube), just to see how its images affect you. Reeling from a 16-year-old commercial for a long-gone LG smartphone, as well as countless cataclysmic videos online, “Crush” opens on a stack of familiar analog samples inside a hydraulic press. A turntable. A metronome. A trumpet. Angry Bird. A pressure ball with big eyes, ready to pop.

The machine comes to life, bringing death to artefacts. Rising from the wreckage: iPad Pro, the thinnest ever, is capable of doing all the other junk, but (this part isn't in the ad) with a little help from generative artificial intelligence. The frame.

If Apple has a belated interest in the comfortably pejorative phrase “generative AI,” generative AI is based on scraping and collecting existing work online, rarely compensating whoever created it in the first place. The equipment is made. It feeds the software to “train” and humanize, if not human, its creative or practical results.

The tech superpower was late to board this barely regulated bullet train. But the iPad Pro, as equity analyst Dan Ives said on Bloomberg Television on May 11, is the first step in Apple's hoped-for “AI-driven supercycle” of product upgrades.

I spoke with Dallas-based Matt Zoller Seitz about the lasting impact of the “Crush” ad and Apple's focus on creative AI. In addition to being a TV critic for New York magazine and vulture.com.

The following has been edited for clarity and length.

Q: Matt, were you satisfied with Apple's official apology for the “Crush” ad?

A: Let's just say that I would appreciate a more sincere and detailed apology for the sheer provocation of the crime that advertising has done against art and artists. It was more like, “Our bad.” Which to me is just as offensive as the ad.

Q: Most people don't remember the words written in the “1984” Ridley Scott commercial for Macintosh, because it was so visually magical. But the dictator on the video wall had this Orwellian line about the government's “instructions for clearing information.” I felt like the new iPad ad was made under the same guidelines.

A: Did it! And let's not minimize the violence of seeing these beautiful objects destroyed, so delightfully depicted. This is a violation. For those who did not care about the issue, it actually caused some, some deep rebellion in them. In the background of one shot, a framed picture is being destroyed, and I can't stop thinking about it. Someone, a production designer, put a lot of thought into exactly what items would be included, and this was one of them.

I currently have a painting of my mother hanging on the wall behind me. Artists have photos and drawings in their workspace for a reason. For inspiration. It could be a picture made by another artist, it could be a picture of their family, their children. So Apple is making sure that the tokens and mementos that feed artists' work are also crushed?

There is something in the piece I wrote that I didn't say, because I didn't think about it until it was published. You cannot create art with this (iPad Pro) software. But you can create “content” with it. A raw form of something creative, that YouTube and other platforms can take advantage of. I think that's what the ad is really telling us. If we eliminate the artist from the equation, everyone can create their own content. And whoever will pay for it.

I think the use of generative AI is a fundamental shift in how technology is used in relation to the arts. It's not like a word processing program that has a spell check. Or a graphics program where you can draw on the screen with a stylus. It's like Tim Robbins' line in “The Player”: “What an interesting concept to eliminate the writer from the artistic process. If we could just get rid of these actors and directors, we might have something here.”

Q: And that was a generation ago, before Apple! What do you say to people who argue that the “crush” ad was okay, and that generative AI is more than okay, and if it wasn't, it's too late?

A: What I say is this: this technology wouldn't exist without the work of the artists already there. I don't care if they use dead artists to train the software. What hurts me is that writers, artists, musicians, filmmakers who are alive, trying to make a living, are using their work as training. This is intellectual labor and wholesale theft of IP on a scale never seen before. And it's really no different than if we were living in a country where somebody comes along and says, “Well, from now on, all the hard work done by the construction industry, it's going to disappear. We now have these machines, and we've trained them by studying the actions of human construction workers without their knowledge or consent.” Will people take it lying down?

What should at least be the equivalent of a Bill of Rights, governing the release of AI content into the wild. Any image or piece of music or writing produced with the help of AI software should be clearly marked. The onus of proving something fake should not be put on the common man. And anyone whose art, or writing, or music was used to train so-called generative AI, should compensate those companies. Duration

Q: One thing I take to heart with Apple's “Crush” commercial? It's a reminder of the failure of any creative human endeavor, even if it's an ad selling an anti-human view of technology.

A: I saw something on Twitter – I refuse to call it anything else – that I think about a lot. Someone said: “I didn't believe in the concept of a human soul until I saw AI-generated artwork.” I believe in such a thing as a soul. It comes in art, in music, in film. And when a machine makes it? You can tell. If you care, you can tell the difference. This is a big deal, though. I think a lot of people have decided not to care. And these are the people I fear the most.

Michael Phillips is the Tribune critic.